The coordinate system we commonly use is called the Cartesian system, after the French mathematician René Descartes (1596-1650), who developed it in the 17th century. Legend has it that Descartes, who liked to stay in bed until late, was watching a fly on the ceiling from his bed. He wondered how to best describe the fly's location and decided that one of the corners of the ceiling could be used as a reference point.

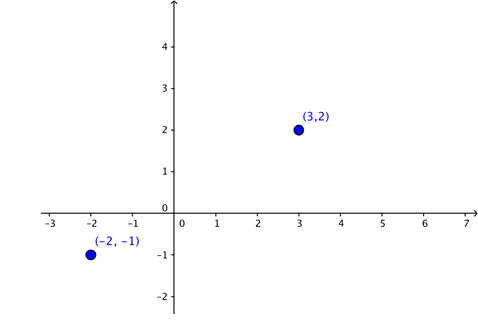

Imagine the ceiling as a rectangle drawn on a piece of paper: taking the left bottom corner as the reference point, you can specify the location of the fly by measuring how far you need to go in the horizontal direction and how far you need to go in the vertical direction to get to it. These two number are the fly's coordinates. Every pair of coordinates specifies a unique point on the ceiling and every point on the ceiling comes with a unique pair of coordinates. It's possible to extend this idea, allowing the axes (the two sides of the room) to become infinitely long in both directions, and using negative numbers to label the bottom part of the vertical axis and the left part of the horizontal axis. That way you can specify all points on an infinite plane.

Descartes' coordinate system created a link between algebra and geometry. Geometric shapes, such as circles, could now be described algebraically using the coordinates of the points that make up the shapes. For example, a circle centred on the point with coordinates $(0,0)$ and of radius $2$ is given by the equation $$x^2+y^2 = 2^2.$$ All points whose coordinates $(x,y)$ satisfy this equation lie on the circle, and all points on the circle have coordinates satisfying the equation. Using such a coordinate system it is possible to solve geometric problems using algebra, and vice versa.

Descartes produced many other works in mathematics, science and philosophy. You might have heard of his famous quote, "I think, therefore I am". And he would undoubtedly have gone on to produce more, had he not died at the relatively young age of 53. His habit of sleeping until 11am had been brutally disrupted by Queen Christina of Sweden, who persuaded him to go to Stockholm in 1649 and wanted to do maths with him at 5 o'clock every morning. Descartes endured the early mornings and the Scandinavian cold for a few months, but eventually contracted pneumonia and died.